After that first drive, I thought everything was fine. The truck ran smoothly, the brakes worked, and nothing seemed off. But a few days later, I noticed a slight pull to one side when braking. Then the battery died overnight even though the alternator was charging. Then I found a small puddle of fluid under the engine that hadn’t been there before. Each issue by itself seemed minor, but together they pointed to a pattern I hadn’t anticipated.

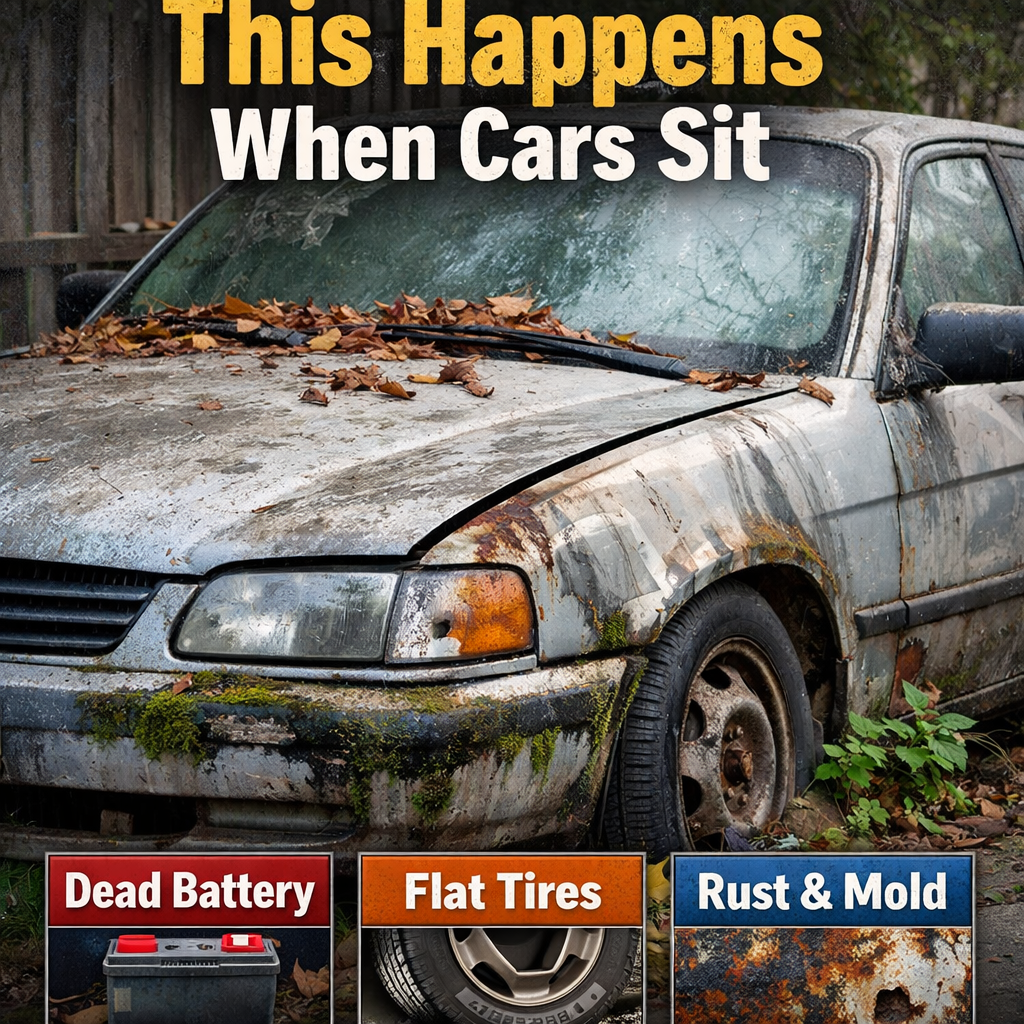

Most people assume that a car sitting unused is better off than one that’s been driven hard. No wear on the engine, no miles added to the odometer, no risk of accidents or abuse. It seems logical that a garaged vehicle should be in excellent condition, especially if it was well-maintained before it was parked. The problem is that cars are designed to be driven regularly, and when they sit for months or years, things start to fail in ways that have nothing to do with mileage.

I’m going to walk through what actually happens to a vehicle during extended storage, why those problems don’t show up immediately when you start driving again, and how to properly evaluate a car that’s been sitting. This isn’t about scaring anyone away from low-mileage vehicles or estate sales. It’s about understanding what you’re really looking at when someone says a car has been parked for a while.

The Situation

My uncle’s truck was a well-maintained half-ton pickup with about forty thousand miles on it. He’d owned it for six years and had done all the scheduled maintenance through the dealership. Oil changes, tire rotations, fluid flushes—everything by the book. When his health declined, the truck went into their two-car garage and sat there while my aunt drove her sedan.

Eight months doesn’t sound like a long time, and in the context of a vehicle’s total lifespan, it shouldn’t be significant. The truck wasn’t exposed to weather. It wasn’t driven hard and then parked hot. It was simply turned off one day and not started again for the better part of a year. My aunt would occasionally go into the garage and start it to make sure the battery didn’t die completely, but she never drove it.

When I took over the process of getting it ready to sell, my assumption was that we’d need a fresh tank of gas, maybe a new battery if the old one had weakened, and a good cleaning. I expected to list it as a well-cared-for, low-mileage vehicle from a one-owner household. The plan seemed straightforward.

The Common Assumption

The conventional wisdom around stored vehicles is that they’re preserved in time. If you park a car with forty thousand miles and leave it alone for a year, you should be able to come back to a car with forty thousand miles that’s essentially unchanged. People think of storage as hitting pause—the vehicle isn’t accumulating wear, so it should be in the same condition it was when parked.

This belief exists because we tend to think of vehicle degradation as a function of use. More miles mean more wear. More starts mean more strain on the battery. More driving means more brake pad consumption, more tire wear, more oil contamination. If you eliminate the use, you should eliminate the degradation. It’s a reasonable assumption if you’re only thinking about mechanical wear from operation.

What people don’t consider is that many vehicle components degrade with time regardless of use. Rubber seals dry out and crack. Fluids break down and lose their protective properties. Gasoline goes stale and leaves deposits. Brake components corrode. Batteries self-discharge. Tires develop flat spots. These processes happen whether the vehicle is driven every day or sitting untouched in a climate-controlled garage.

The other factor is that regular use actually keeps some systems healthy. Engines need to reach operating temperature to burn off moisture and contaminants. Brake rotors need friction to prevent surface rust. Seals need movement to stay pliable. When you remove that regular cycling, you’re not protecting the vehicle—you’re allowing different types of damage to accumulate unchecked.

The Turning Point

The brake pull was the first real indication something was wrong. It wasn’t dramatic, just a slight drift to the right when I pressed the pedal. I initially thought it might be a tire pressure imbalance, but all four tires were inflated correctly. When I took the truck to a shop for a basic inspection before listing it, the mechanic pointed out that the rear brake calipers were sticking.

He explained that when a vehicle sits, the brake calipers can seize partially because the pistons and slides corrode in place. The corrosion isn’t enough to lock the brakes completely, but it creates uneven braking force between the wheels. That explained the pull. Fixing it meant replacing both rear calipers and the brake fluid, which had absorbed moisture while sitting and was no longer at the right boiling point.

The battery issue came next. Even after a full charge, it wouldn’t hold voltage overnight. The mechanic tested it and said the plates inside had sulfated from sitting in a partially discharged state. My aunt’s occasional starts had kept it from dying completely, but they hadn’t prevented the internal damage that happens when a battery doesn’t go through full charge and discharge cycles regularly.

Then we found the fluid leak. It was a slow seep from the rear main seal, which had dried out and lost its flexibility. The seal had been fine when the truck was driven regularly because the engine heat and oil flow kept the rubber pliable. Eight months of sitting had allowed it to harden and crack just enough to let oil pass through.

What Most People Miss

Cars have dozens of rubber components—seals, gaskets, hoses, belts, bushings, motor mounts. Rubber degrades through a process called oxidation, where exposure to oxygen breaks down the molecular structure. This happens faster when rubber is flexed and heated, but it also happens when rubber sits static in the presence of air. The difference is that regular use cycles the rubber through expansion and contraction, which can actually slow the formation of cracks by preventing the material from hardening in one position.

When a car sits, rubber seals settle into a fixed shape. If they’re compressed, they stay compressed. If they’re dry, they stay dry. When you finally start the vehicle and ask those seals to do their job again—expanding, contracting, sealing against pressure—they often can’t. They’ve lost their elasticity. The result is leaks that appear shortly after a stored vehicle returns to service.

Fluids are another hidden issue. Engine oil contains additives that suspend contaminants and prevent corrosion. Over time, even in a sealed crankcase, those additives settle out and lose effectiveness. Coolant is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs water from the air, which dilutes its protective properties and can lead to internal corrosion. Brake fluid is even worse—it pulls moisture through microscopic pores in rubber hoses, and that moisture lowers the fluid’s boiling point and corrodes brake components from the inside.

Gasoline degrades rapidly when stored. The lighter hydrocarbons evaporate, leaving behind heavier compounds that don’t combust as efficiently. After a few months, gas can varnish and gum up fuel injectors, fuel pumps, and carburetors if the vehicle is old enough to have one. Even if the engine starts and runs, the degraded fuel can cause rough idling, hesitation, and deposits that affect long-term performance.

Tires develop flat spots when a vehicle sits in one position for weeks or months. The weight of the vehicle compresses the rubber at the contact patch, and if the tire doesn’t rotate, that deformation can become semi-permanent. In some cases, the flat spot will round out after a few miles of driving. In others, especially with older or cheaper tires, the deformation stays, causing vibration at highway speeds.

Electrical systems suffer too. Modern vehicles have dozens of electronic modules that draw small amounts of current even when the car is off. These parasitic draws are normal and manageable when the vehicle is driven regularly and the battery is recharged. When the vehicle sits, those draws slowly deplete the battery. If the battery voltage drops below a certain threshold, the modules can lose their programming or suffer damage. Even if the vehicle starts after a jump, you might find that systems like the radio presets, climate control settings, or even transmission shift points need to be relearned.

Consequences of Ignoring It

In the short term, driving a vehicle that’s been sitting without addressing these issues leads to a cascade of small failures. The battery dies at inconvenient times. The brakes perform inconsistently. Fluid leaks create messes and potential damage to driveways or garage floors. The rough running from degraded fuel might smooth out, or it might leave deposits that cause long-term driveability issues.

In the long term, the consequences become more expensive. A seized caliper that’s not replaced can damage the brake rotor, turning a few hundred dollar repair into a more costly one. A leaking seal can allow enough oil to escape that the engine runs low, risking serious damage if you don’t notice in time. Degraded coolant can corrode the radiator, heater core, or water pump, leading to cooling system failures that could have been prevented with a simple fluid change.

There’s also the safety concern. Brakes that don’t function evenly increase stopping distances and make the vehicle harder to control in emergency situations. Tires with flat spots or dry-rotted sidewalls are more likely to fail at speed. Electrical gremlins can cause unpredictable behavior, from stalling to loss of power steering or braking assist in vehicles with electronic systems.

For someone buying a vehicle that’s been sitting, these consequences translate directly into unexpected costs. You might purchase what looks like a low-mileage, well-maintained car, only to discover that it needs thousands of dollars in work to be truly reliable. The seller might not even be aware of the problems if they haven’t driven the vehicle enough to expose them.

How to Check or Think About This Properly

When evaluating a vehicle that’s been stored or sitting unused, the first question to ask is how long it’s been parked and under what conditions. A car sitting for three months in a heated garage is different from one that’s been outside for a year. Get specific details about whether it was started periodically, how often, and whether it was actually driven or just idled in place.

Ask about the maintenance that was done before storage and whether any preservation steps were taken. Did the owner add fuel stabilizer? Did they put the vehicle on jack stands to keep weight off the tires? Did they disconnect the battery or use a trickle charger? These steps aren’t always necessary for short-term storage, but their presence or absence tells you how seriously the owner took the process.

If you’re able to inspect the vehicle before purchase, pay attention to signs of sitting. Check the tires for flat spots, cracks, or dry rot. Look at rubber hoses and belts for surface cracking. Open the oil cap and look for a milky residue, which indicates moisture contamination. Check the battery voltage and note how the engine starts—does it crank slowly or fire right up?

Take the vehicle for a test drive that includes full-speed braking from highway speeds in a safe area. You’re checking for brake pull, vibration, or any unusual pedal feel. Listen for strange noises that might indicate seized components or degraded bushings. Pay attention to how the transmission shifts—long periods of sitting can affect transmission fluid and clutch packs in automatic transmissions.

If the vehicle has been sitting for more than six months, budget for a complete fluid service regardless of what the maintenance records show. Oil, coolant, brake fluid, transmission fluid, and differential fluid should all be changed. The fuel tank should be drained and filled with fresh gas, or at minimum, treated with a high concentration of fuel system cleaner to address any varnish or deposits.

For tires, check the date codes. Tires older than six years should be replaced regardless of tread depth, and if the vehicle has been sitting on the same spot for months, inspect carefully for flat spots that haven’t rounded out after driving. Don’t assume that good-looking tread means the tires are safe.

Common Myths and Misunderstandings

Myth one: Starting a car every week prevents storage damage. Starting the engine without driving prevents the battery from dying completely, but it doesn’t protect against most storage-related issues. The engine needs to reach full operating temperature and stay there for at least twenty minutes to burn off moisture and keep seals conditioned. Idling for five minutes doesn’t accomplish this and can actually cause more harm by allowing condensation to build up in the exhaust system and oil.

Myth two: Low mileage always means better condition. A ten-year-old car with thirty thousand miles might seem like a great find, but if those miles were accumulated in the first three years and the car has been sitting for the last seven, it’s likely in worse condition than a ten-year-old car with a hundred thousand miles that’s been driven regularly and maintained properly. Consistent use is often better for longevity than sporadic use or long periods of inactivity.

Myth three: Garage storage eliminates weather-related damage. Storing a vehicle in a garage protects the paint and interior from UV damage and keeps rain and snow off the body, but it doesn’t prevent the internal degradation of fluids, rubber, and batteries. A garaged car will have a nicer exterior than one stored outside, but the mechanical condition can be just as compromised if the storage period was long enough.

Myth four: If it starts and drives, it’s fine. Many storage-related problems don’t manifest immediately. A car might start right up after months of sitting and seem to drive normally for the first few miles. The issues show up later, after heat cycles, after the initial fuel in the system burns through, or after you’ve put enough miles on it to stress the compromised components. A test drive is necessary but not sufficient to catch everything.

Myth five: Only old cars are affected by sitting. Modern vehicles have more complex electrical systems, tighter manufacturing tolerances, and different fluid formulations than older cars, but they’re still subject to the same basic physics. Rubber still degrades, fluids still break down, and batteries still discharge. A three-year-old luxury car that’s been parked for a year can have just as many storage-related issues as a fifteen-year-old economy car in the same situation.

When It Matters Most (And When It Doesn’t)

This matters most when you’re buying a vehicle with an unclear or inconsistent use pattern. An estate sale, a car from a widow or widower who no longer drives, a vehicle that was parked due to a military deployment or long-term travel—these situations raise red flags that should trigger deeper questions about how long it’s been sitting and what condition it’s really in.

It also matters for vehicles that will continue to sit after you purchase them. If you’re buying a second car that you’ll only drive occasionally, or a project vehicle you plan to restore slowly, or a recreational vehicle that only comes out a few times a year, you need to think about storage preparation and maintenance to prevent the same issues from developing on your watch.

It matters less for vehicles that have been sitting for very short periods—a few weeks to maybe two months. At that timeframe, most of the degradation processes haven’t progressed far enough to cause significant problems. A fresh tank of gas and a battery check are usually sufficient to get the vehicle back into regular service without major concerns.

It also matters less if the vehicle was properly prepared for storage. If the owner used fuel stabilizer, maintained the battery with a tender, changed all fluids before parking it, and stored it in a controlled environment, many of the typical issues can be minimized or avoided entirely. The presence of these precautions tells you the owner understood what they were doing and took the vehicle’s long-term condition seriously.

Final Takeaway

The key insight is that vehicles deteriorate with time, not just with use. Sitting doesn’t preserve a car in amber—it just changes the type of wear that occurs. Instead of friction and heat wearing down moving parts, you get corrosion, oxidation, and chemical degradation affecting stationary components and fluids. Both types of wear are real, and both require attention.

When you’re evaluating a vehicle that’s been stored or sitting unused, you need to approach it with the understanding that hidden damage is likely present, even if the exterior condition and mileage suggest otherwise. Budget accordingly, ask the right questions, and don’t assume that a clean history report and low miles mean you’re getting a trouble-free vehicle. Sometimes the best-looking cars on paper are the ones that need the most work.

We eventually got my uncle’s truck sorted out and sold it, but not before spending more than I’d anticipated on brake components, battery, fluids, and a seal replacement. The buyer got a good truck, and we were honest about the work we’d done and why it was necessary. What I took away from that experience was a permanent skepticism about any vehicle that’s been sitting for more than a couple months. Now when I see a low-mileage car that’s been parked, I don’t see a pristine survivor—I see a list of components that have been aging silently and will likely need attention soon. That perspective has saved me from several purchases I would have regretted.